2022: Funishment

Agent Charlie

[Casefiles of a five-year-old investigator and his Native father, ‘Bristles’]

THE NUMBERS

Bristles shows me a circle divided into twelve hours. These are governed by a long line and a short line which he calls ‘hands’, even though they have no fingers or wrists.

‘Why are there twelve hours, daddy?’ I say.

‘Because it’s a clock,’ says Bristles.

‘But why twelve?’

He thinks. ‘That’s a good question.’

Twelve is a number, and numbers are like deities to Natives. They sacrifice sixty minutes to an hour, seven days to a week, and twelve months to a year; they worship inches and ounces, feet and yards, dollars and Euros, meters and miles.

Yet something has gone wrong: every day I see the Natives shaking their heads, saying ‘…you have to follow the Numbers…the Numbers are too high…’

It’s a confusing religion. No wonder the gods are angry.

SUMMARY

So far, so good:

No one knows I’m in charge.

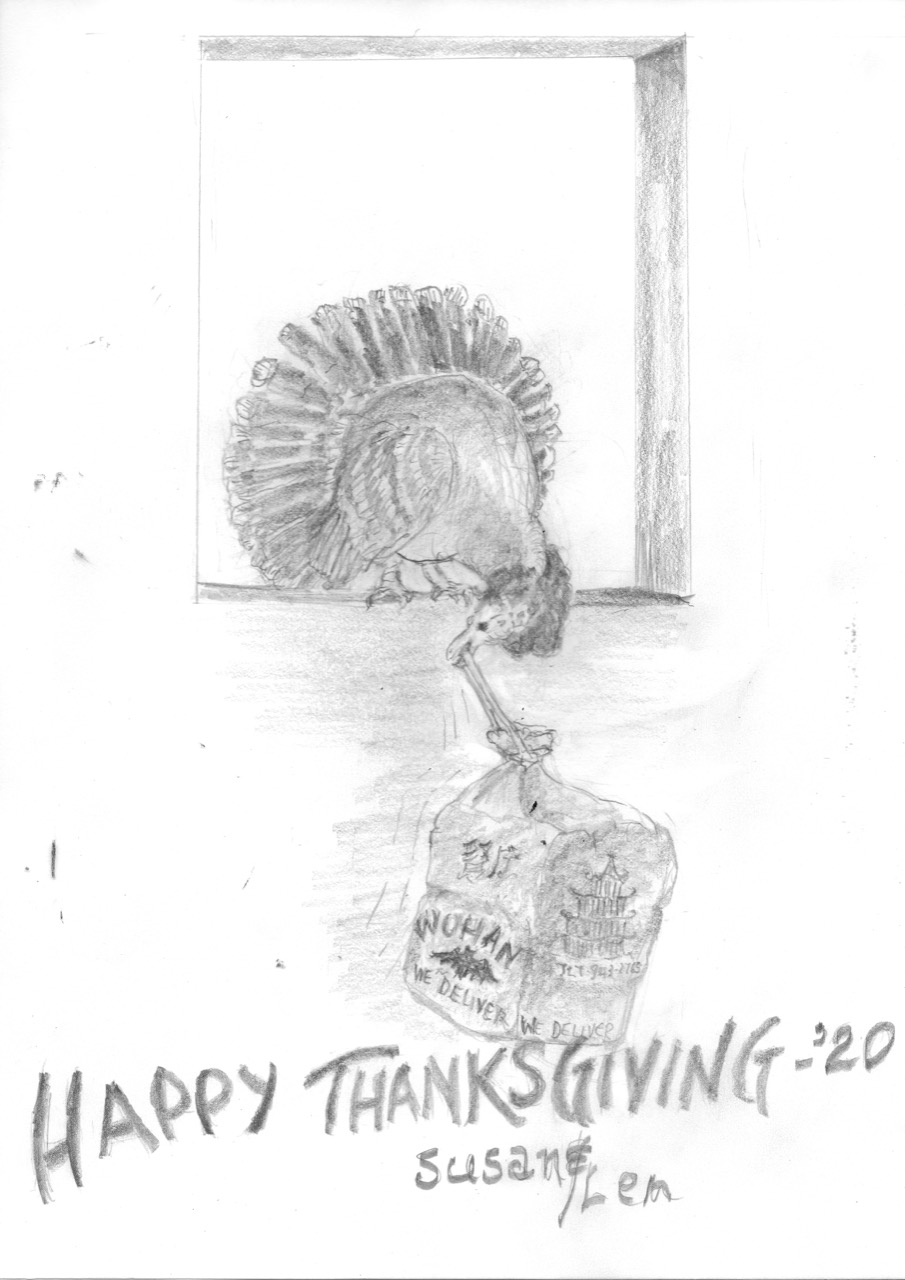

The Father’s Perspective: Second Jab

At the time of writing, almost 190,000 people on the Island have been fully vaccinated. The Superintendant of Public Health has stated that some people are choosing not to get vaccinated, ‘for various reasons.’

One of those reasons may be a fear of side effects from the second injection.

I arrived early at the clinic. Just like before, there was no waiting, none of the queues I’d seen at hospital. I even had the same nurse, standing in the doorway, ready with the needle.

I felt more wound up about the second jab. Just get it over with, I was thinking. I’ve never liked needles, and I’d heard the second dose of Pfizer had stronger side-effects than the first shot.

As I sat down, the nurse asked for my least favourite arm. She slipped the cap off the needle, I turned away and hardly felt a thing.

I asked her about any symptoms to watch out for.

‘It depends on the person,’ she said. ‘Expect aches, fever and tiredness.’

‘Does that mean it’s working, that I’m getting a good immune response?’

She blinked at me.

‘Rest…take Panadol.’

A blond woman with a black mask came into the treatment room as I left; I sat in the courtyard outside, and set 15 minutes on my phone for my cool-off period. Soon the woman came out and sat opposite, holding her arm. We exchanged an amused look. Perhaps this is an unexpected benefit of wearing masks—we’ve all developed stronger eyebrows, for expressing the excruciating irony of our times.

I sat back, prodding my arm. An ache was already settling in. So how was this second dose going to compare to the first one?

Sequels are rarely better than the original: for many critics Godfather II is the best in the trilogy, but I prefer the first one. Technically I rate Empire Strikes Back over Star Wars, but both movies are very different. Then there’s Toy Story II and first trilogy Spiderman II. In many ways, Covid is in itself a sequel: but is “CoV-2” a simplification, as any virus is a result of millions of mutations?

The blonde woman left after five minutes. Perhaps I’d overdone the eyebrows.

Soon my alarm pinged and I went home. That evening I had a Zoom call with a Dutch schoolfriend, who was feeling exultant after he’d ‘bagged’ his first vaccine jab. For months, Phil had been feeling depressed about the slow ‘roll-out’ in Holland; he’d called that morning to confirm an appointment in seven days, when the woman on the other end said, ‘We have a spare booking in thirty minutes.’

Phil jumped up, threw on some shoes, grabbed his keys and cycled like hell across Amsterdam. I have an image of him in his striped pyjamas, his dressing gown streaming out behind him, his wheels whizzing as he raced to the clinic.

Phil asked me how I was feeling, after the second vaccine, and I said, ‘A bit stoned.’

I went to bed feeling optimistic.

At 3am I woke up feeling cold. I was lying next to something heavy and painful. I realised it was my arm.

This must be working, I thought.

May on the Island is not cold, but I was shivering as I got out of bed. I shuffled down the hallway, shaking. My throat felt like I was hanging in the grip of the Predator alien. Swollen lymph nodes?

I sat down in the bathroom and read some Calvin and Hobbes. The book shook in my lap, then gradually subsided. I didn’t feel so bad, but then I got up and the shakes returned.

It’s working, it’s working, it’s working, I thought, as I shuffled back to bed. I popped some paracetamol and lay down with my new friend, the amazing pulsating arm.

As I tried to sleep I compared Pfizer with other vaccines I’d taken. I must have been thirteen when I took my BCG [for Tuberculosis]. I remembered standing in line with other boys, waiting for the initial ‘tester’ dose. A nurse briskly ‘stamped’ my shoulder, leaving a three-pronged welt.

Then we all had a week of waiting to see if the pin-prints would swell up, indicating we had a natural response, and didn’t need the dreaded injection. Every morning we woke up, hoping for a blossoming on our shoulders; as far as I can remember, no one experienced a miracle.

So we went back to the nurse for the needle. Later I experienced some painful side effects, as my friends—including Phil— repeatedly punched my arm. Apart from that, I can’t remember any problems.

I’ve taken a lot of travel vaccines since school. Three years ago I signed up for a boat trip in Borneo, for which I had to take the Yellow Fever vaccine. On the night before the flight I felt my usual pre-trip nerves, so I partied with a friend and ate some fish and chips.

Early the next morning I was horribly sick in the bathroom. At the time I’d thought it was a combination of partying and nerves—or was it a late reaction to the Yellow Fever jab? According to the NHS website, side effects from that vaccination include headaches, muscle pain, raised temperature, and joint ache but no nausea or vomiting. So it was probably too much battered fish.

The day after my second Pfizer jab I felt like I’d aged thirty years. I shuffled around the apartment, feeling rotten; I’d read that exercising the aching arm may be a help, so I managed ten press ups. Later I found out that exercising is not recommended after the jab.

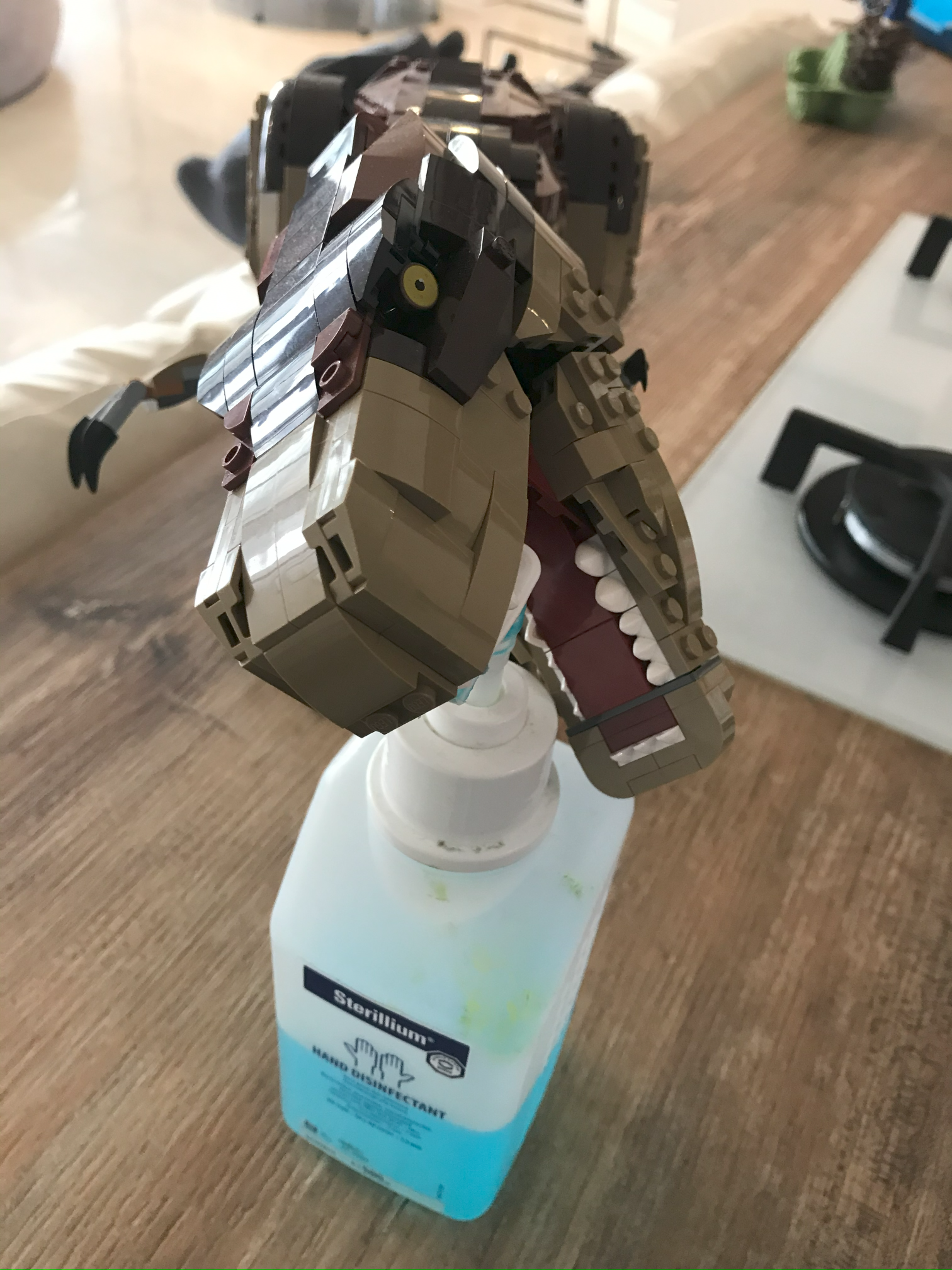

That day I ate and drank and read Calvin & Hobbes. I tried building my Lego piano, but I could barely lift a piece. Feeling dizzy, I texted my friend the Immunologist: Wow, the second Pfizer has really wiped me out.

His reply was swift:

Haha it does that

That was exactly what I needed to read. The next day I woke up feeling 60%, and now, a week later, I feel fine. The second Pfizer dose made me feel lousy but thankfully, as with most sequels, the nausea was short-lived.

Agent Charlie

[Casefiles of a five-year-old investigator and his Native father, ‘Bristles’]

THE OTHER SIDE

I’m colouring in a chameleon when

‘Damn it!’ yells Bristles.

I look up from my drawing.

‘What’s wrong, daddy?’

Bristles is scowling at a disposable mask.

‘I paid five Euros for these useless masks.’

He looks at one side, then the other. He looks confused, frustrated. I try to help:

‘It’s white, daddy.’

‘Exactly! It’s white—on both sides.’ He throws it down. ‘How can I tell which side is the outside?’

This is a compelling dilemma.

‘This. Is. What. Happens,’ he growls. ‘When you give control to the virologists.’

I prod the mask. It feels like soft paper. I scribble.

‘When will it bloody end?’ says Bristles. ‘When will we finally get our freedoms? When can we stop—’

He stops and looks down at me; I look up at him, my pen paused over the mask.

‘What are you doing?’ he says softly.

I carry on drawing. ‘A spider.’

My spider has blue legs with a red head. Bristles picks up the mask before I’ve finished the picture.

‘Charlie, that’s BRILLIANT!’

Excited, he gives me another mask. ‘Draw something else— but on the other side. The outside.’

I give him a green pen. ‘You can do one too, daddy.’

‘I will!’

Soon we have drawn some tiger-eating bees, a purple elephant, two sunsets, some sleeping rhinos and a tree full of pianos. Bristles is grinning from ear to ear, as he personalises his beloved masks.

BEACH CRIME

I’m on a secret quest.

Bristles stretches out on the sand, pulls down his mask and sighs happily. The sun is rising and the beach is deserted, save for a faraway Native father and two Agents playing in the sand. I carry on digging, determined to find the treasure first.

‘Excuse me, sir.’

Two policemen are standing over us. I drop the spade. They’ve caught me!

Bristles sits up in his Speedos.

‘Good morning,’ he says.

I try to look casual as the policemen examine his face.

‘Sir, you’re not wearing your mask.’

‘Huh?’

‘Your mask.’

‘But I’m stationary.’

Excellent: Bristles is distracting them. Slowly, I pick up my shovel.

‘Stationary, sir?’

The younger policeman is writing on a notepad. He looks nice but his older companion is silent and hostile. It’s a good cop/bad cop thing.

My father has a cover story: previous policemen had told him that Natives are allowed to have lowered masks provided they were ‘stationary’, i.e sitting or standing still, at which time they are also allowed to eat, drink and smoke.

‘You see?’ He points down at his towel: ‘I am stationary.’

‘Aha,’ says the policeman. ‘But you are on a beach.’

My father looks around, confused.

‘It’s because of the virus, daddy,’ I say.

‘So I can pull the mask down if I’m smoking,’ says Bristles. ‘But you’re fining me for sunbathing?’

‘Sir, I’m going to give you a Warning,’ says the younger policeman.

A Warning! We’re doomed!

Bristles points at me: ‘How about him?’

I dig frantically. Shut up shut up—

‘No, no,’ says Good Cop, magnanimously. ‘He doesn’t have to wear it.’

My father pulls up his mask, and to my relief the officers start to walk off.

‘Just a minute,’ says Bristles.

They stop. Oh no!

My father holds out his hand.

‘Can I have a receipt?’

Bad Cop glares at him. There’s a baleful silence.

The fool! He’s pushed them too far!

Good Cop gives him a small piece of paper.

‘How about if I want to swim?’ says my father.

Shut up shut up shut up—

‘You still have to wear your mask in the sea,’ says the nice policeman, ‘until the water’s up to—’

He holds his palm up to his waist.

‘—here.’

‘Wow,’ says Bristles.

‘I know, it’s stupid,’ says the policeman.

‘It’s because of the virus,’ I say, and continue digging.

SUMMARY

So far, so good:

No one knows I’m in charge.

The Father’s Perspective: A March for Human Rights

It was a beautiful sunny afternoon at the big fountain. The air was sweet with the smell of caramel popcorn, parents were out with their children, Mariah Carey was singing Christmas songs from the carousels, and I was feeling edgy about the protest march.

Was I going to take off my mask, and break the Law? On impulse, I wrote ‘SHOW ME THE SCIENCE’ on my mask, which I hoped would kick off some conversations about the absence of scientific studies justifying the wearing of masks outside.

But where were the protestors? All I had to do was follow the trail of police uniforms to a man holding a red flag. He was obviously the leader of the march, as his face was naked and four police officers in black masks were gathered around him.

Against the backdrop of the ferris wheel, the march leader was wearing a black jacket and jeans, and extremely clean red trainers. Very patiently, an older police officer was telling him, ‘It’s a crime…it’s a crime…it’s a crime.’

After a while the leader turned away and tucked a fine into his pocket, like a winning lottery ticket: ‘I am going to Court…it’s what I wanted.’ His thick glasses magnified his eyes, making them look huge. I asked him his name and what he wanted to achieve today, and he said, ‘I haven’t worn a mask for two years.’

A young mother pushed past me, cutting through the protestors with her baby carriage. Toddlers watched on, curious, as a man with a manbun fired up a bullhorn and boomed: ‘Let us breathe!’

The leader spoke to the crowd: ‘Wear your mask…don’t come to court like me…at 2:30 we will start marching.’ Meanwhile the police were talking to a thin, bare-faced woman with an American accent. I was about to chat with her but then I read her placard: THE FINAL VARIANT IS CALLED COMMUNISM.

There were lots of interesting signs at the protest. An older gentleman was carrying ‘Nuremburg codes protects us from medical TYRANNY’, while a girl in khaki leggings posed beside, ‘We DON’T want your Liberty we want are BIRTH RIGHTS’ [sic].

Two guys were holding yellow boards with ‘Where there is Risk there must be Choice’ and ‘The TRUTH is coming for you…you have nowhere to HIDE.’ I asked the sign holder, ‘What is ‘The TRUTH?’’

He leaned closer. ‘Excuse me?’

‘The TRUTH!’ I raised my voice. ‘What is ‘The TRUTH?’’

He looked at the board, then pointed at his fellow protestor:

‘Ask him.’

His companion wore a grey scarf over his mouth.

‘What is ‘The TRUTH?’’ I said.

‘All of this,’ he said, in a fervent English accent. ‘It’s all for The Great Reset.’

We left the fountain at exactly 2:30, as the organisers played ‘We’re not going to take it any more’, from a speaker on wheels. For one wonderful moment Twisted Sister competed with Maria Carey from the carousel.

The march went down a big shopping street, with around seventy to a hundred people carrying signs, and the bullhorn booming: ‘Let us breathe, let us breathe…’ Outside McDonalds the music changed to ‘We Are the World’, and a passing tourist muttered, ‘Science Deniers.’

I asked a policewoman if the organisers had had to get a permit for the march, and she said yes but didn’t respond to my follow-up, ‘This is quite calm, isn’t it?’ There didn’t seem to be much support or interest from the passers-by.

The demonstration stopped outside a shopping centre, and the leader gave a speech.

I picked up, ‘Vaccina…criminali…humanity…’

‘Ecco…’ agreed the demonstrators. ‘Ecco…’

‘Emergencia…radicali, democratico!’

I think I heard ‘Magna Carta’, but I couldn’t be sure. As I left the demonstration, the sounds of the bullhorn faded behind me: ‘Let us breathe…let us breathe…let us breathe…’

I weighed up my feelings about the march. While I admire people who stand up for what they believe in, I’d expected them to focus on the follies of outdoor masks, instead of other [albeit related] complaints. It was billed as a ‘Peaceful March for Human Rights’, so I should have known better.

At the top of the high street I counted twenty people either without masks or ‘at half-mask’, with their noses showing. There was no one to catch them: the march seemed to have sucked up all the police. I realised that my mask had expanded as I was wearing it, so only the words, ‘SHOW ME’ were now visible, with ‘THE SCIENCE’ tucked away under my chin.

As I headed home, I wondered whether the restrictions could have been fairer; could the authorities have declared shopping and tourist areas ‘masked zones’, and left less populated areas alone?

The police had been very calm and professional during the protest. On the day the restriction came into effect I’d seen a member of the local constabulary patrolling my uncrowded harbour, sniffing out naked faces; I hadn’t seen any officers in my neighbourhood since June, the last time citizens were fined for wearing masks outside.

Agent Charlie

[Casefiles of a four-year-old investigator and his Native father, ‘Bristles’]

THE HUNTER

It’s a hot day in the park. Bristles urges me to hydrate, multiple times, then suddenly says, ‘Let’s go, Charlie.’

‘But I want to stay.’

‘Five more minutes, ok?’

He sets his timer to five minutes, but we leave after two. As we walk back towards the car, Bristles is looking around, sniffing the air. We stop at a low building with padlocks across the doors.

‘Oh, great.’

We walk on, and come to a hut with a sign on the shutters.

‘Damn it!’

‘What’s wrong, Dad-dee?’ I say.

‘I need to pee.’

There’s tension in his voice. Everywhere we go, the toilets are locked. He quickens his pace; my father is hunting, returning to his primal roots.

‘Dad-dee, why don’t you use a tree?’

Bristles looks around. ‘…someone will see me.’

My father is a stealthy hunter.

We come up to a promenade, running along a busy road.

I find a stick and play music on some railings:

‘RATA TA TA TA…’

‘Come on, Charlie,’ says Bristles.

RATATATATATATATATA

‘Charlie, quicker, please!’

My father is a slave, both to his bladder and to his primitive society; why can’t Natives wear personal sanitation devices, like infant Agents and astronauts? Instead they cultivate sewers.

My stick rattles the railings:

RATA TATA TATA

‘Charlie, hurry up.’

RATA TATA, RATA TATA

Bristles stops and puts his cap on my head.

‘Hey, wanna go on my shoulders?’

‘Yes, Daddy!’

He lifts me up and I bounce along as he crosses the road. Now we’re moving faster. Bristles looks forlornly at a closed hotel, then peers through the windows of cafes; everywhere, we see chairs piled up against toilet doors, yellow tape, red notices.

‘Bloody restrictions,’ he mutters.

Everywhere is locked. No one is welcoming Bristles inside. Now he’s stepping from one foot to the other, increasingly desperate; the hunter has become the hunted. Finally, he can’t take any more. We step into a big café and Bristles squeezes my knee.

‘Don’t say anything, ok?’

‘Yes, Daddy.’

We mime zipping our mouths and bump fists.

Bristles marches up to the counter. The teenage assistant looks up from his phone, and my father points up at me.

‘My son needs to go to the toilet.’

‘No, I don’t, daddy,’ I say.

My father squeezes my knee: ‘He really needs to go.’

The teenager frowns. ‘Usually we don’t allow—’

‘He really really needs to go,’ implores my father.

‘But daddy—’

‘Shh!’

He gives the boy an imploring look, as though I’m ready to explode.

‘OK.’ The teenager picks up a big key and leads us to the back of the cafe. ‘But be quick.’

We hustle through a door and come into a dim hotel lobby.

A nasty voice nearby:

‘Sir?’

Bristles finds a series of doors with pictures of male and female Natives on them. The nasty voice rings out, louder:

‘Excuse me, SIR!’

Wearily, Bristles turns. A stout woman is glaring from behind a Reception desk.

‘You can’t use those.’

My father jerks a thumb up at me.

‘He’s had an accident.’

‘No, I haven’t, daddy…’

My father raises his voice. ‘Please, it’s an emergency.’

‘But, sir—’

‘Thank you!’

He lunges into the bathroom.

BONK

He hits my head on the doorframe. Bristles takes me down, breathing heavily.

‘Oh Jesus, oh Charlie I’m sorry are you all right—’

‘But I don’t need to go to the bathroom, daddy.’

He checks my head. I’m wearing his cap so I wasn’t injured. My father makes it into the cubicle and I hear a great sigh.

After he’s washed his hands, he bends down and looks into my eyes.

‘Charlie, that was called a ‘white lie.’ It’s only used for BIG emergencies, ok?’

‘Ok.’

He squeezes my hand.

‘And only adults can use them.’

We bump fists.

Bristles is smiling angelically as we exit, past the scowling receptionist [‘Thank you SO much!’] past the nervous teenager [‘Cheers!’] and over to his car, where he straps me in and turns on the aircon. We eat some dark chocolate and Bristles sings to some bad music; I’ve rarely seen him so happy.

Now we have a long journey home. My father hands me my water bottle and turns on the ignition.

‘Daddy,’ I say.

Bristles indicates and pulls out. Almost immediately, we are blocked in by solid traffic, but my father is free of his torment, so he doesn’t care.

‘Dad-dee?’

‘What is it, Charlie?’

‘Daddy.’

‘Yes. What is it?’

‘I need to pee.’

SUMMARY

So far, so good:

No one knows I’m in charge.

The Father’s Perspective: The Children in the Gym

Charlie’s father volunteers at a summer school during the pandemic

It was thirty-five degrees and there were no fans or aircon for the sixteen kids running around the school gym. At one point, a seven-year old boy came up and said something to me.

I bent down. ‘What?’

He pulled down his mask.

‘It’s hot,’ he said, and went back to chasing a ball. Later, a doleful girl with wet hair just stopped playing.

‘What’s wrong?’ I said.

‘It’s too hot.’

I sat next to the supervisor for the class.

‘Yesterday I was working out in a gym,’ I said. ‘It has big fans and air con, and no one had to wear masks, so why do these children have to wear them?’

‘I’m a believer in kids wearing masks, she said. ‘If just one of them has Covid, they’ll pass it on, and then they’ll all be in quarantine.’

‘But we know that kids don’t suffer from ‘Severe Covid’ as much as adults, we’ve vaccinated all the ‘vulnerables’, so why are we doing this to these children?’

‘Kids have died from Covid.’

‘It’s very rare, though,’ I said.

‘Anyway, I don’t want to get it from them.’ She sat back, exhaling heavily. ‘I’m a diabetic.’

This seemed to end the conversation, as if challenging someone’s medical status was forbidden. I found her attitude arrogant and controlling, and I suspected her diabetes was diet-related.

I considered her position: I can understand how it’s impossible to rely on children to follow adult guidelines of social distancing and relentlessly sterilising hands, and masks must seem to be the best answer.

But I can’t help feeling a sense of shame. As an adult, I feel complicit in putting children through two years of restrictions for a virus which, statistically, is unlikely to cause them long-term harm.

I’m grateful that I’m in my forties during the Pandemic; I feel really sorry for the eighteen to thirty-year olds who’ve had their youth disrupted, when they are clearly in a lower risk group. If I’d been that age in 2021 I would have been much more reluctant to follow all the ‘guidelines’.

I’m grateful that my son is only five, and he can roll with it with more grace than I can. It must be much harder for older kids; at worst, the last two years’ restrictions have increased rates of childhood eating disorders, mental illness and suicide. Children have missed the community of their friends and all the other things school has to offer, from music, dance, sport, cookery and drama, even lessons.

Of course, not all kids are gutted at missing school. When I heard that certain pupils were using lemon juice to fake ‘positive’ readings on PCR tests, my first reaction was, ‘Wow, they’ll go far.’

Yes, faking the tests is wrong and causes chaos, but I couldn’t help admiring kids who use their initiative to game a system which has condemned them to months of home schooling, or sitting in classrooms wearing masks.

I’m pro-vaccine and protecting people, but I think it’s important to question policies. Personally, I can put up with 2021’s social irritations, from showers randomly shutting at sports clubs, to the litany of cancelled flights and social events.

But I get angry when I see regulations inflicted by adults on children which don’t seem to be saving anyone. If such a high proportion of the Island’s population has been vaccinated, why are children wearing masks in a hot gym? Are we trying to achieve a form of herd immunity, or ‘treading water’ while we wait for vaccines to kick in, and we know more about the Delta variant?

Back in the gym, the supervisor inhaled and sat up.

‘When they run,’ she said. ‘They can pull their masks down.’

‘Yes, but do they?’

‘Hey everyone!’ she called out. ‘Don’t forget to pull your mask down when you run.’

Few of the children remembered this in their excitement. It all seemed self-defeating: surely when you’re running along and breathing hard, you spread more ‘aerosols’ then when you’re standing still?

Ultimately, I’m glad that the kids in the gym showed a greater spirit and resilience than whining grown-ups like me. Young people are our most precious ‘assets’, and we need to make their lives as safe and as fun as possible.

At least the children in the gym have frequent water breaks. Now, two weeks after I’d pressed for them, the organiser of the sports programme has provided some fans, so the gym has its own ‘cooling station’, an oasis in the humidity. I’m amazed it has taken so long, but I’m also glad it has finally happened.

Agent Charlie

[Casefiles of a four-year-old investigator and his Native father, ‘Bristles’]

SERENGETI

‘This morning, Charlie, you’re going to witness one of the dumbest migrations on Earth.’

Bristles waits for me to strap in my seat belt, then hands me his laptop.

‘These animals are called ‘wildebeest.’

‘Widder bees!’

On the screen a line of grey animals is trotting across a hot orange plain.

‘Wow daddy there’s more than thirty thousand billion wider-bees in Africa!’

Whistling, my father sits behind the wheel and we start driving to school. It’s raining, but I can see lots and lots of cars outside the window; Natives enjoy traveling at the same time, presumably to strengthen community spirit.

The bandy-legged animals jostle in the dust, bucking and snorting at flies. I’m amazed they stay in the convoy.

‘Daddy, where are they all going?’

Bristles stares at a line of cars forming to our right.

‘Good question,’ he says.

On the screen, the grey-bearded wildebeest reach a river. One of them stands on an outcrop, looking out across the milky water.

Bristles slows down, frowning.

‘…now what?’

Traffic thickens around us. My father stops the car, frowning at the rain.

‘…we should’ve ended this, by now.’

‘Ended what, daddy?’

He taps the steering wheel, shaking his head.

‘…two years and hardly a car on the road, cleaner air, everyone working from home…so why not make it permanent? Two days in the office, three days at home, simple.’

He stares into the murky traffic.

‘We haven’t evolved.’

‘What does ‘evolved’ mean, daddy?’

‘Change,’ he says faintly. ‘No one’s really changed.’

A wildebeest jumps into the water, then three others. A baby animal follows them, leaping to keep out of the frothing current; I watch it, willing it on to the far side. Finally it reaches the shallows, panting, and starts to climb the bank.

Something lunges out and grabs its leg.

‘Daddy!’ I yell.

Bristles jumps.

‘What’s wrong?’

‘Daddy, daddy, a crocoldile!’

‘Where? Where?’

‘In the river, daddy!’

Bristles puts his forehead on the steering wheel. He looks at the stationary cars, then at his watch. He curses.

‘Now we’re going to be late for school.’

Squealing from the Serengeti: jagged teeth pulling the wildebeest under the water. Some of its friends pause on the shore, sniffing and grunting, confused.

Bristles cranes his neck, squinting into the rain.

‘So that’s why…’

Up ahead a grey car is lying on its side, smashed by a green truck. I see jagged metal at the point of impact.

The drivers stand and look at the crash, dazed and docile.

The wildebeest stare into the water, confused and uncertain.

Bristles slowly shakes his head.

‘We just haven’t evolved.’

FREEDOM DAY

The moment I step out of school, my father rips the mask from my face.

‘This is it, Charlie— freedom!’

‘But daddy—’

Back in his apartment Bristles hold up my last mask, disgusted; we can see all of the fascinating fluids, mucus, dirt, dust, bacteria and viruses I’ve been collecting today. It’s like a molecular diary of my face.

‘Make an explosion, daddy!’

My father torches the mask with a butane lighter— but it’s too slimy to ignite.

‘…damn you…just…’

Bristles rips off the strings and slam dunks it in the bin.

‘…die!’

One fellow Agent at another school managed to vomit in his mask, so his teachers put him in a room on his own, without food or water. When his mother came to pick him up, she found him sitting on a stool with his clothes covered in sick; she shook her head, angry and sad at ‘…what we’ve come to.’

SUMMARY

So far, so good:

No one knows I’m in charge.

FUNISHMENT: A Father’s Final Words from Covid 19

My niece has contracted Omicron. At eleven, she’s too young to take a vaccine in the UK. I’m feeling a little nervous as I FaceTime her in quarantine.

She looks listless. I ask her how she’s doing.

‘I have no energy,’ she says. ‘And a fever.’

The Russians have two kind of envy: ‘black’ envy, and ‘white’ envy. I’m feeling the friendly ‘white’ variety as I tell her, ‘Chances are, you could end up with much stronger immunity than me.’

Even though my niece is the first in my family to contract the virus, I’m sensing that Covid 19 is nearing its end. Now hospital numbers are dropping throughout Europe, the pandemic seems to be waning. So, are we really in an ‘endemic’ phase—or am I being premature?

Perhaps it depends on how many letters are left in the Greek alphabet. Sometimes I feel like a commentator on CNN, eager to ‘call’ the winner of a Presidential election, but wary of calling the wrong candidate.

Summarising two years, a plague and almost six million deaths feels like condensing a world war into a few pages, so I’m focusing on language. Much of 2020/2021 I’d gladly forget, but the parts I want to remember are anchored in words and phrases—some new, but some old and previously unknown to me.

CORONAUSEA

Towards the end of 2021, my family had a game: see how long you could get through a day, or even a conversation, without mentioning Covid-19. I was saturated with imaginative theories and predictions, and it felt surreal having my experiences reflected both locally and globally, as presidents and talk-show hosts were all preoccupied with the same topic.

For me, Covid was interesting to talk about and boring to live through. This is particularly true for one of my vaccinated friends, who is currently undergoing his eighth quarantine, despite never having tested positive himself.

Despite the boredom and the travel frustration, I remember an explosion of creative videos online— lovely opera coming from lock-downed balconies in Italy, or a family coming together to record charming parodies of pop songs [the Marsh family]. Perhaps that is why I’m now addicted to YouTube.

For some, government policy in Italy and Austria verged on the despotic; I imagine sociologists of the future being fascinated by the imposition of mandatory measures, and doctors being upset about the abrupt transition from individualized medicine to ‘one size fits all’ vaccination policies.

There were some crazy stories. One friend freaked me out with news of a Swiss variant, before adding, ‘Don’t worry, Peter— you can’t afford it.’ I heard of a mountain where you could ski unrestricted on the Swiss slopes, but you had to wear a mask if you were skiing down the French side. And who said, ‘Wearing a mask while you’re driving on your own is like wearing a seatbelt in the park’?

In the future, will ‘coronausea’ give way to ‘coronostalgia’? I have an impressive collection of masks, with zippers, shark teeth, famous paintings, divers and even a sensual pair of lips; will some people miss wearing masks, washing hands and being face-gunned by temperature-checkers in supermarkets?

‘PLANDEMIC’

The writer Yuval Noah Harari beautifully described the dawning age of science as ‘the discovery of ignorance’. I sense there was a great deal of ignorance exposed by this ‘novel’ virus.

For me, the strongest metaphor for the sheer scale of the problem was the Ever Given cargo ship, wedged across the Suez Canal in March 2021. It looked massive and immovable, just like Covid 19. At the time, I sensed there was never a way of ‘beating’ the virus, only of minimising its impact.

Did governments and health councils have a preferred outcome, or was it just ‘wait and see’? I tried to remain rational about the Great Experiment we’re living through, with two years of winging it and ‘Following the Science’; I never trusted ‘Big Pharma’, but my gut feeling regarding humanity favours opportunism over ‘evil plans to take over the world’.

I decided I trusted my medically-trained family members over some of my friends who’ve magically became virologists after watching videos on You Tube. My grandfather, PB Medawar’s quote that “a virus is a piece of bad news wrapped up in protein” had a renaissance in 2020, while my father, a retired radiologist, remembers Polio as “…another virus that crippled or killed, and is now extinct, worldwide…there were opponents of immunization then, too. Jerks.”

For final reassurance, I needed that Great Physician, Arnold Schwarzenegger, to guide me: ‘…all of the virologists and doctors and epidemiologists have studied diseases and vaccines for their entire lives, so I listen to them…if you have a heart attack, you don’t check your Facebook group, you call an ambulance.’

So I bumped elbows, kept my distance and washed my vegetables. I avoided crowds and wore masks on the beach, feeling like an idiot, in the drive to ‘keep everybody safe’. But then, following the contemptuous behaviour of [my] UK government, I developed doubts. By late 2021 I was teetering on the edge of a dozen rabbit holes, YouTubing doctors in bow ties, questioning public policy.

My Italian statistician friend’s claim that ‘There are lies, damned lies and Covid statistics’ strengthened my distrust of numbers, which could be used to strengthen any argument. My attitude towards vaccines may have been different if I’d contracted Covid in 2020, as I never explicitly disagreed with the benefits of natural immunity over vaccination.

Now, as data grows supporting the long-lasting, polyclonal protection afforded by Omicron, I’m wary that the conspiracy theorists were right all along; will the unvaccinated sell their untainted blood for billions? Will the vaccinated become graphite-controlled 5G zombies with increased risk of mortality via embarrassment?

OMNICRON

Since I read reports in January 2022 from South Africa, suggesting that the latest variant would go everywhere fast, I couldn’t avoid adding the ‘omni’ to this omnipresent virus. The predominant adjective for Omicron was ‘mild’, hopefully spreading swift natural immunity with blessedly reduced hospitalization; I couldn’t help feeling that Mankind dodged a bullet with this variant.

My favourite quote came from a conversation between two doctors in Uganda: ‘The Omicron variant is the vaccine that we failed to make.’ [from John Campbell, Great News from Africa, YouTube [27.1.2022]

FUNISHMENT

I became addicted to medical reports; their language enriched my vocabulary. Soon I could discuss ‘immunological ‘naïvity’ to SARS Cov-2, clonal expansion of B Cells specific for antigenic epitopes, nucleocapsid-specific T-Cells, and pre-existing spike cross-reactive memory T-Cells’, without understanding any of it.

Some familiar words felt corrupted. I used to like ‘bubbles’ before they were used to divide people, and ‘breakthrough’, once a heroic advance, now refers to a fully vaccinated person being infected by the virus [a ‘vaccine’ breakthrough]. Thankfully no one is using the nauseating phrase ‘New Normal’ any more.

In addition to ‘Coveat’, ‘Cobo’ and ‘Angstipation’, I’ve come up with ‘Funishment’: over two years of puritanical caution, having a party could be ‘funished’ by quarantine, a fine, or hospitalisation. See also hangover, herpes and Boris Johnson.

CHILD VECTORS

In 2021 a paediatrician friend asserted, ‘If adult mortality were as low as childhood mortality with Covid, we would never be talking about a pandemic at all.’ Since then I saw my son isolated at home for a fortnight because he was in the same room as a positive case, and then released after consistently testing negative.

Over the past two years I felt sorry for younger generations, from university students to school children, suffering for a disease which predominantly affected older people. By late 2021 I was unconvinced by arguments that restricting children would prevent them from passing the virus on to adults, not when such a huge majority of older people were vaccinated.

In the end, I was chastened by my son’s cheerfulness in isolation. Perhaps he was enjoying a fortnight of not wearing a mask and being snapped at by paranoid grown-ups with handy-wipes.

FINAL WORDS

According to the naturalist Colin Tudge,

“…. [viruses] are major drivers in all of nature, that may determine the shape and direction of an entire ecosystem….it may be that if there were no parasites, there would be no sex… Without sex to mix the genes, creatures like us…could not have evolved at all.

It seems indeed that we are as we are because our retrospective ancestors had to cope with disease.”

[Colin Tudge The Secret Life of Trees]

Essentially, his view is that our conflict with viruses have helped push our evolution. Cold comfort for the day-to-day horrors and irritations of the pandemic, but perhaps we can use this concept to improve as a species.

The core aim of governments throughout 2020/21 seemed to have been protecting health systems, and preventing Intensive Care Units from being over-run with sick patients. So should we now invest in building new hospitals, buying more equipment, training contingency staff and improving the working lives of doctors?

For me, the key is how to help the next generation: how can we improve life for the children who’ve sat through hot unventilated lessons, played sport in masks and only seen their friends through digitised lessons at home?

One common word in the Pandemic was ‘comorbidities’, a disease or medical condition which can significantly worsen a patients’ health if they have Covid. My friend, a Canadian author, tells me, ‘I’m 43, fit and I eat healthy, but require immunosuppressive medication…Omicron is not mild for everyone, and those of us with health issues and disabilities have essentially been deemed worth sacrificing.’ He’s not asking for endless lockdowns, just a little kindness and consideration.

Among the most commonly mentioned comorbidities are diabetes and hypertension. Hypertension, unfortunately, has rarely-noticed symptoms, which led to the fear of unknown numbers of vulnerable people blocking up the hospitals.

This ‘tip of the iceberg’ concept was a strong justification for restrictions. There were many arguments for and against masks, lockdowns and vaccines, and yet the dangers of bad diets were chronic long before 2019. Along with age, obesity was probably the most commonly quoted risk factor for severe Covid; now that huge resources have been thrown at controlling Covid, why not push for another campaign against controlling obesity?

Why not teach children more about how to cook for themselves, and how to limit the intake of salty, oily or sugared junk which proliferates our supermarkets? Why not emphasize that takeaways are a treat, not part of a regular diet?

I strongly believe in the benefits of regular sports and fitness, providing fun, social contact, and increased energy. Losing the right to play sport during the Pandemic, while all the takeaways remained open, and junk food mopeds circled the Island, was one of the most frustrating aspects of the Pandemic for me.

Sport has been one of the few undisputed pleasures of my life; I don’t need a doctor to tell me that encouraging the blood to flow faster round my body helps in all areas of physical health, and I don’t need to read the ingredients for a Big Mac to know that it may make me feel lousy the next day.

Many people avoid talking about Covid now— perhaps they’re sick of it. But we need to be ready for future pandemics; I haven’t seen any reports of Viral Research Labs being shut down, or an abolition of the horrific ‘Wet Markets’. How are we better prepared now, than in 2020?

Our population is growing exponentially, and we’ll keep on encountering new diseases which spread through our urban and travel matrices, following on from HIV, Spanish Flu, Avian Flu and Covid 19. For now, we should maintain a state of virological preparedness and enjoy life as much as possible…before we get wiped out by Omega.

Let’s push on with our evolution, working from home more to reduce traffic and air pollution, and promoting an educational system suitable for the 21st Century. And why not tackle grotesque social inequality, worldwide destruction of forests for agriculture, over-fishing and plastic pollution while we’re at it?

Five days after her Omicron diagnosis my niece took an antigen test: for a happy thirty seconds it was negative, and then…positive. When I FaceTime she’s playing Battleships against her mum, and she looks rosy-cheeked and healthy.

‘How did you sleep last night?’ I ask.

‘Better. My sore throat has gone…still got a runny nose.’

‘So it’s basically just like…a cold..?’

She grins: ‘Yeah.’

ENDS