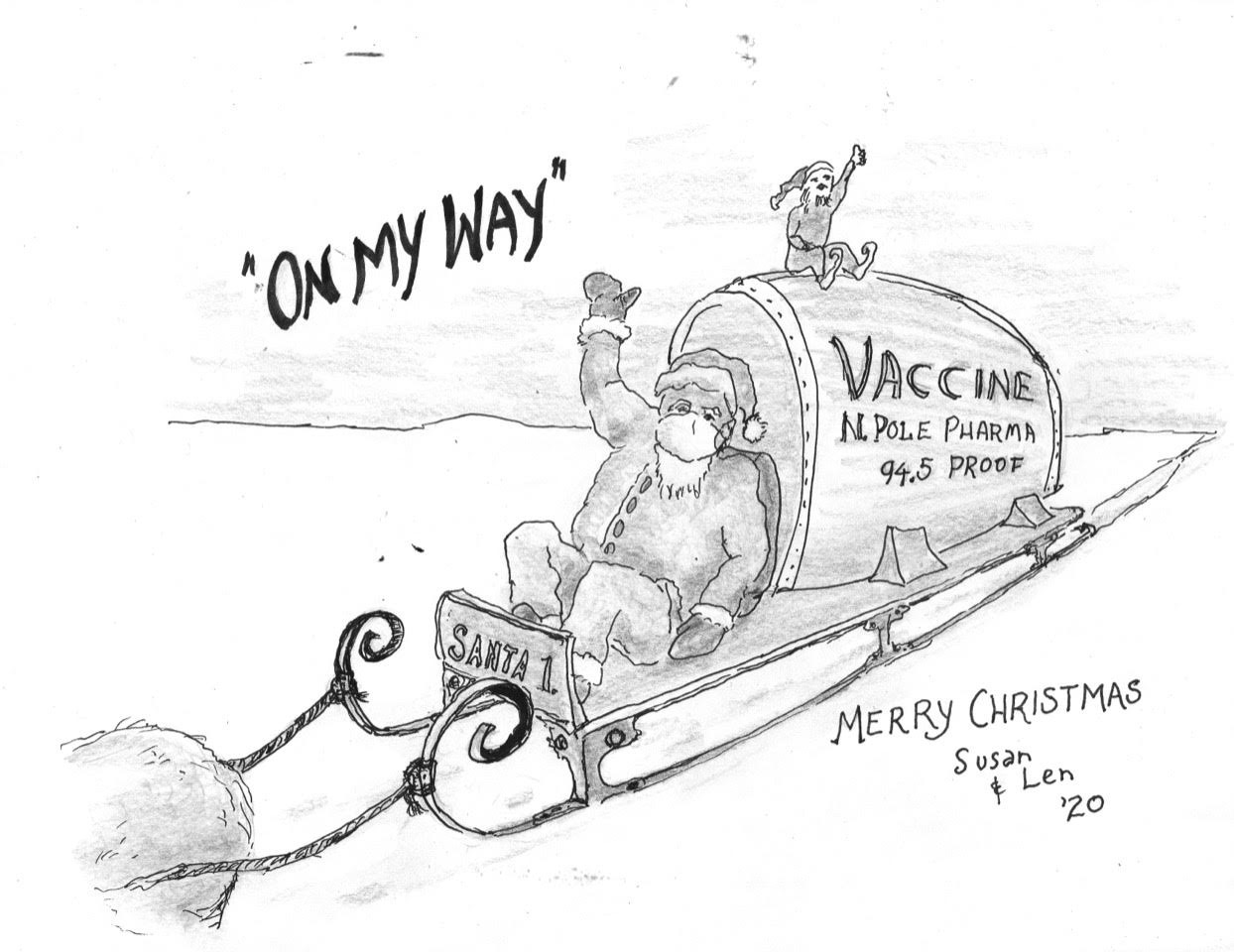

2021: Coveat

COVEAT: The Father’s Perspective

April

Today I got my first vaccine.

I lucked out with Pfizer, the first drug to climb the Pandemic Everest. It had been around for the longest, so I was surfing the crest of a wave, enjoying one of Mankind’s greatest achievements, up there with Mo Salah and the Moon Landing.

But there’s a Coveat.

The immunity afforded by a vaccine might wear off with time; the vaccine might not protect against those ghouls of the future, variants. Covid’s caveat bludgeons my hope with a familiar disappointment.

So why take the vaccine at all? Why not just wait to get naturally infected by Covid, with my 99% chance of survival, so I can develop my own antibodies?

According to my friend, the Immunologist

I would definitely advise getting vaccinated ahead of natural immunity. Response to infection is very unpredictable: it could go anywhere from severe pneumonia with lung inflammation and ITU admission or death, to asymptomatic infection or a mild sore throat. Your immune response would be equally unpredictable and probably not very long lasting or incomplete. The process behind making the vaccine is to basically identify those vaccine proteins that do not lead to inflammation and disease but at the same time trigger off a robust, long-lasting immune response. The Pfizer contains messenger RNA signals that will generate similar proteins and mimic the presence of the virus without all the mess of actually getting sick, and this leads to immunity.

So this ‘targeting’ acts like an e-mail—gives us a message, teaches us something new and gets thrown away? My fundamental reason for taking the vaccine was that my faith in science was stronger than my faith in its alternatives: I don’t want vulnerable people to die in hospital, and (to a certain degree) I accept the sacrifice of personal freedoms for the greater good.

Many of the people I love and trust have been vaccinated, and as yet no one has grown an extra head. I’m not comfortable with the lack of long-term studies, yet my rock-solid hatred of masks and a yearning for non-annoying travel outweigh my fear of the risks of vaccination.

As I sat in a shaded courtyard in Paola, awaiting my fizzy Pfizer, I reflected on how the tiny pain of an injection promised the return of hugs, and an end to the chronic loneliness of the pandemic year.

Once my ID had been checked I was shown into a small office, where a nice Indian nurse injected Pfizer into my shoulder muscle. I was grateful she didn’t twist the needle, like the PCR people twist the nasal swab, and also that she didn’t ‘miss’ the muscle, a mistake which may have explained the rare incidence of blood clots in the Astra Zenica jabs.

Very soon I was back out in the courtyard, feeling faintly heroic. I was fighting back against a Common Enemy. This is the nearest my generation have come to a War, and I was ‘playing my part’ in the effort. Now it was official: there was my name on the vaccine card, misspelt.

My arm was aching for the next two days. I may have been more tired than usual—

hard to tell. I was looking forward to getting the second jab over and done with, and setting up my own HappyVax Supper Club. According to recent Covid Symptom Tracking Data in the UK, the chances of suffering from the virus after one dose of vaccine is 1 in 100,000, which goes down to 1 in 150,000 after two doses.

But there’s a Coveat.

There’s always a Coveat: while vaccines are slashing hospital admission rates, they won’t 100% stop you spreading the filthy disease. Yet ultimately, in the words of the Immunologist, taking the vaccine

‘…is a no-Brainer in the current climate.’

Agent Charlie

[Casefiles of a four-year-old investigator and his Native father ‘Bristles’]

Mystery Word

Bristles and I put on our masks to go to a café to buy some fresh air. Viruses are limited by height, so by sitting we avoid infection. We take off our masks while passers-by gaze enviously at the free breathers at their privileged altitude. I listen to these Natives speaking through their masks, and notice a pattern.

‘Daddy, why are all the people saying the same word?’

‘What word?’

I look at him and smile. ‘Guess…’

‘Is it ’Corona?’

‘No.’

‘Covid?’

‘No…’

‘Come on, Charlie: you can tell me. What’s the word?’

A Native brings a black drink for Bristles and an orange drink for me. I pour the orange liquid from one glass to another.

Bristles sips his drink thoughtfully.

‘Is the word…’safe’?

‘No.’

‘Is it ‘‘sorry?’’

I blow down the straw.

‘No.’

‘’Please?’’

‘No.’

‘’Thanks?’’

‘No.’

He looks around the café.

‘…and this is the word that everyone is saying? Everyone in the whole world?’

‘Yes.’

He runs off a list of words, all wrong. Finally, he shakes his head.

‘OK, I give up.’

I blow down my straw.

‘Charlie, you can tell me now.’

Bubbles are fascinating.

‘Really? You’re not going to tell me?

Utterly fascinating.

‘Fine.’

Bristles yawns, stretches and smiles.

‘Do you want some ice cream?

I jump up. ‘Yes! Yes! Yes!’

‘Then tell me the word.’

I sit back down, annoyed. Bristles taps my hand.

‘No word, no ice cream.’

I blow bubbles.

‘Ah well…’ Bristles puts on his mask. ‘Come on, let’s go.’

I lace my mask over one ear, then the other.

‘You know the word,’ I say.

‘Huh?’

‘There!’

My voice is muted by the mask.

‘What word? Huh?’

‘That’s it!’ I shout.

He leans closer.

‘Huh?’

I take off my mask.

‘That’s the word that everyone is saying!’

In a moment of sublime evolution, my father sees how the virus has distilled human communication to one single, muffled huh?

But he’s forgotten about the ice cream.

‘Strawberry,’ I say.

‘Huh?’ says Bristles.

I’m so proud of him.

MASK-FATIGUE

Sometimes when we’re walking outside, Bristles breaks into a jog. Or he sits down on the pavement to eat, or steals someone’s dog. Or he pretends to suddenly enjoy nicotine.

The policeman passes us by in the harbour, then stops and comes back:

‘Put on your mask, sir.’

‘But I’m smoking.’

For a moment the policeman seems satisfied that my father is protecting his health. Then he gives a little smile.

‘Smoking, sir?’

‘Yes, that’s right—’ Bristles holds out the cigarette. ‘Here’.

‘But sir,’ says the policeman. ‘You need to light it.’

‘Oh, ok. Yeah. Forgot.’ Bristles starts to move off, but the policeman holds up a hand.

‘Allow me.’ He holds out a lighter.

Bristles freezes.

‘Or perhaps you’d prefer the 100 Euro fine?’ says the policeman.

They look at each other, like chess players. The cop holds up the lighter. He flicks out a flame. Slowly, Bristles bends over and touches his cigarette to the end. He puffs the smoke out.

The cop watches him.

Bristles inhales confidently—then doubles up, retching and wheezing.

The cop smiles.

‘Bad cough, sir?’

He hands Bristles a ticket.

‘Perhaps you need to take a test.’

SUMMARY

So far, so good:

No one knows I’m in charge.

MEA COVID: NEW WORDS FROM THE PANDEMIC

June

The Pandemic has been horrible for a lot of people, but it has also generated a wealth of funny videos, cartoons and portmanteaux. A ‘portmanteau’ combines two existing words to make a new one, such as ‘podcast’ [iPod + broadcast]. Over the past year I came up with ‘Angstipation, ‘Cobo’ and ‘Coveat’, as well as ‘Mea Covid’; many other words evolved online, on sites such as Urban Dictionary.

COBO

At the height of restrictions, lonely people sat in the streets, eating off paper plates, swigging cans of beer and belching at other ‘Covid Hobos’. Grown men chatted illegally behind bushes, taking turns to bob up and check for police.

COVEAT

This refers to the relaxing of a restriction, immediately followed by a caveat. For example: ‘Vaccinated people may appear in public without masks on, BUT they can only walk with one other person, who must also be vaccinated.’

See also my updated idiom: ‘There’s a tunnel at the end of the light.’

ANGSTIPATION

Eighteen months ago, I remember one of my friends saying, ‘Wow, dude, we’re actually living through a pandemic.’ It felt like a war, an invisible invasion. There was an immediate impact on so many private lives, presenting us with so many layers of uncertainty.

Back then we were paranoid about hugging and devoted to washing vegetables. We were ‘angstipated’, with ‘angst’ and ‘constipation’ forming a state of persistent, hardened worry.

MEA COVID

Not a portmanteau, but a play on ‘Mea Culpa’, in which no one takes responsibility for anything. When you ask why the shoe salesman is giving you a sheath for your sock, he will shrug and say, ‘Because of The Covid, sir.’ Is there any point in questioning how a respiratory disease can be transmitted through the toes? No.

When you ask the waitress why you can’t pay with a card, she won’t say, ‘Because the bank doesn’t trust this restaurant’; instead, she’ll shrug and say, ‘The Covid.’ It’s a magical word which exonerates its user from all blame.

‘My Covid’ also points to how distinctly the virus affects each individual. For many people, the national response to Coronavirus, curtailing luxuries such as travel and concerts, elicits an intense, prolonged irritation; but for others it’s caused redundancies and collapsed businesses, missed education, overworked medical wards and the sheer horror of being unable to hug dying relatives in hospital.

VIARUS

One big current question is the origin of Covid 19—was it a ‘zoonotic’ transmission from animals to humans via a revolting ‘wet-market’? The comedian Jon Stewart disagrees: ‘You know who we could ask? The Wuhan Novel Respiratory Coronavirus lab.’

He said it is too much of a coincidence that a lab researching these illnesses was at the same place where the outbreak occurred, while the host of the show, Stephen Colbert, said that it was equally likely that they put the lab there because it’s where the diseases had occurred before [The Late Show, 14/6/2021].

Whatever you believe in, one thing is certain: Covid 19 is very effective at spreading through human populations, ‘via – us’. This phrase was coined by my friend, a Chilean composer.

QUARANTINI

On my Island there was never a time when we couldn’t drive from one place to the other, or had to justify the ‘essential’ nature of our journeys to the authorities. But we still needed plenty of ‘quarantinis’— a regular Martini, drunk alone.

I spent both of my quarantines working from home, practicing The Imperial March from Star Wars on my keyboard, bouncing on a trampoline to lift my spirits and watching way too much YouTube. I should have spent more time learning how to make cocktails.

LOCKDOWN SYNDROME

A play on ‘Stockholm Syndrome’, during which multiple quarantinis are consumed, with many ‘snaccidents’ (you start with a couple of biscuits and end up finishing the whole pack). There was never a lockdown on the Island, but quarantine was infectious: in April I heard that 10,000 people were confined to their homes on the Island because they’d been in contact with people who’d tested positive.

AIRGASM

My favourite portmanteau from the Pandemic: when you rip off your mask after seven hours in an airplane and take that first blissful rush of air, you have an ‘airgasm’.

Some of my friends enjoyed the lack of tourists in 2020/2021, but holidays often resulted in disaster. How many horror stories have I heard of travellers stranded in airports, crippled by bizarre paperwork, or driving frantically across-country to catch the last ferry before the borders clanged shut?

I had my own Corona travel disaster. Following the ‘UK-strain’ panic of January 2021, the Island’s government began allowing only nationals and residents back into the country. As I stood in the queue at Heathrow, I gazed down at my expired Residence Card. It wasn’t an issue when I’d left the Island, as normally I only use my passport for travelling, but now I felt uneasy.

I’d applied for the new residence permit in July 2020, and I’d been promised a new card, but had heard nothing for six months. No one had told me to travel with the confirmation papers, now safely tucked away in my filing cabinet on the Island.

I stood in the queue at Heathrow, thinking, It’s the twenty-first century: surely I’ll be in the system?

I wasn’t.

The airline gave me Covid helpline info and threw me off the flight. I ended up staying for a week with an NHS friend in Bristol, during the harshest winter lockdown of the Pandemic.

I had to stay quiet for fear of nosy neighbours tipping off the police; I felt like a fugitive, hiding from the Covid Gestapo. I spent a week grimly calling and emailing the authorities on the Island; in the end, I got two of my friends to break into my apartment into photograph the papers required for me to travel.

Once I’d received helpful letters of transit from the British Consulate, I could move on to joyfully calculating the exact time I needed between taking a PCR, processing the PCR and getting on a plane.

A week after being thrown off the flight I stood in another queue at Heathrow, gripping a folder-full of documents. I was tense all the way through Customs and Security, all the way to Luqa airport; only when I got into my apartment did I rip off my mask, enjoy a wonderful airgasm and start mixing up a fortnight of quarantinis.

Agent Charlie

[Casefiles of a four-year-old investigator and his Native mother, ‘Smooth’, and his father, ‘Bristles’]

QUARANTINE

Smooth drives me down to the sea, where we stand on a windy wall opposite my father’s apartment.

Bristles appears on the balcony.

‘Daddee!’ I cry.

‘Hi Charlie!’

He seems excited to see me, like a hungry monkey at the zoo. We can’t touch Bristles because he is in ‘quarantine.’ This is when Natives incarcerate each other for traveling.

‘Hey Charlie,’ says my father. ‘You’ll never guess what Jarmalendi has been up to.’

He disappears back into his flat.

‘Jarmalendi?’ says Smooth.

Bristles reappears with a T-Rex, made of hundreds of pieces of Lego.

‘Look what Jarmalendi’s made, Charlie.’

He holds up a golden egg.

‘Wowww…’ I say. ‘What’s inside?’

‘Aha! You’ll find out next time I see you.’

‘But I want to know now.’

‘You can’t,’ says Bristles. ‘It’s…gestating.’

‘Now, Daddy.’

Bristles looks aggrieved, but Smooth is more understanding:

‘Charlie doesn’t do the future.’

It’s getting cold, so I wave goodbye to my father.

Next time we come, I’ll throw him a banana.

TESTING: Bristles drives Smooth and me from the airport. We come to a parking lot and wait in a line of cars. Soon we arrive at a white office on wheels. A Native wearing a blue plastic smock, a scary mask and a visor comes up to the car with a clipboard.

Bristles winds down the window with a smile.

‘I’ll have a Big Mac, Large Fries and a shake.’

Smooth puts her head in her hands and sinks in her seat.

The Native cocks his head, confused.

‘ID Card,’ he says in a muffled voice.

Bristles holds up a piece of plastic.

‘Turn your head,’ says the Native. ‘This may be uncomfortable.’

The Native inserts the ‘Big Mac, Large Fries and a shake’ all the way up Bristles’ nostril. My father goes rigid, gasping and quivering like a fish on a line. The Native counts down from five to zero, twisting.

Then he comes round the car and Smooth tilts her head. More twisting. She goes rigid, quivers and gasps.

The scary Native points at me. I go cold, shrink back in my seat.

His muffled voice:

‘What about him?’

SUMMARY

So far, so good:

No one knows I’m in charge.

ENDS 2021