Scotland’s Covid inquiry is destroying the case for lockdowns

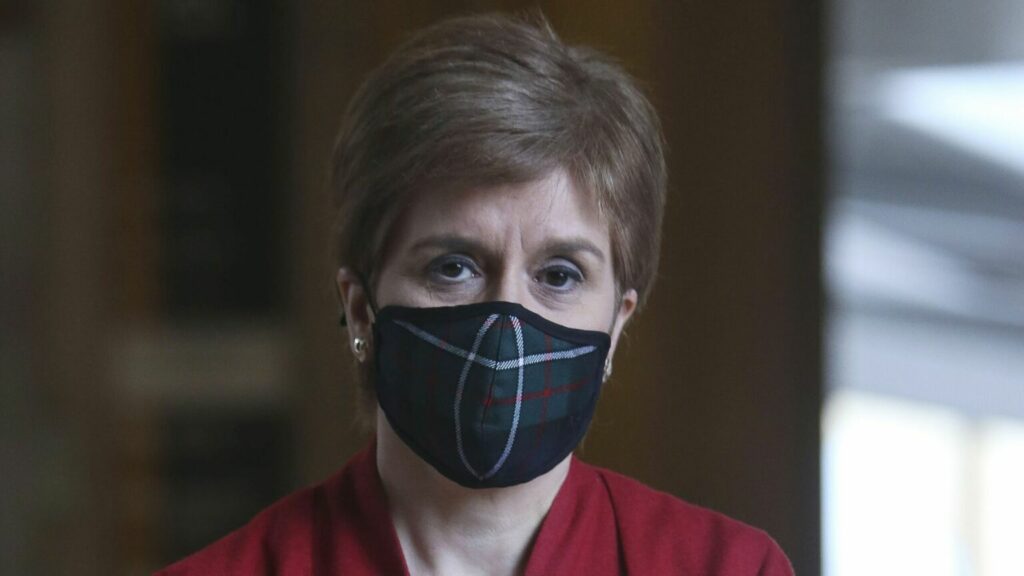

Nicola Sturgeon’s longer, harder restrictions were all for nothing.

Throughout the Covid pandemic, Scotland’s then first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, posed as a cross between Mother Teresa and John Knox, compassionately but sternly protecting her people, as much from Boris Johnson’s mayhem as from the virus.

As a result, Scottish lockdowns were longer and harsher than those in England. People in Scotland were constrained to within five miles of home when no such restrictions existed south of the border. Mask requirements persisted far longer and vaccine passports were demanded more widely in Scotland – not just for large events, but even for ‘sexual-entertainment venues’, which are not known for facilitating mass gatherings.

When, in summer 2020, Covid rates dipped low, Sturgeon flirted with following New Zealand’s strict Zero Covid approach. Once Covid predictably resurged that autumn, Scotland effectively closed the border with England to ‘non-essential’ travel. By February 2021, anyone arriving from anywhere abroad had to fork out £1,750 for hotel quarantine. Faced with the later Omicron wave in November 2021, Sturgeon again threatened to seal the border with England.

Scotland’s approach to Covid was often simply deranged. In early 2022, Sturgeon even mooted sawing the bottom off classroom doors to blow the virus away. This idea was taken very seriously until fire regulations put paid to it.

Yet despite their stringency, Scotland’s Covid policies achieved little. In the two years from the start of the pandemic to the tail of the Omicron wave in spring 2022, Scotland averaged 23.9 excess deaths per million weekly. That was by far the highest in the UK, with Wales suffering 22.9 excess deaths per million, Northern Ireland 18.8 and England 18.6.

Given the Scottish state’s pro-lockdown bias, it’s remarkable that Scotland’s official Covid inquiry, which is being carried out separately to the UK inquiry, opened last month with a bluntly factual narrative by Dr Ashley Croft. Croft is a public-health infection epidemiologist who has spent most of his career working for the army and Ministry of Defence (MoD) and who now practises from Harley Street as a medico-legal expert witness.

He told the inquiry that:

‘In 2020, there was scientific evidence to support the use of some of the physical measures (eg, frequent handwashing, the use of PPE in hospital settings) adopted against Covid-19. For other measures (eg, face-mask mandates outside of healthcare settings, lockdowns, social distancing, test, trace and isolate measures), there was either insufficient evidence in 2020 to support their use – or alternatively, no evidence; the evidence base has not changed materially in the intervening three years. It has been argued that the restrictive measures introduced during the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in individual, societal and economic harm that was avoidable and that should not have occurred.’

I’d agree entirely. As Sweden’s already-concluded Covid inquiry found, ‘Several countries which did impose lockdowns… had “significantly worse outcomes” than Sweden’. It also found that the restriction of individual freedom was ‘hardly defensible other than in the face of very extreme threats’.

Croft is similarly downboat about the vaccines, which I think is unwarranted. He says it ‘remains unclear as to whether or not Covid-19 vaccination has resulted in fewer deaths from Covid-19’. But it seems fairly clear that vaccines did break the link between cases and deaths in the spring and summer of 2021. Still, Croft is right to say that the protection they offered was brief and incomplete. Long before vaccine passports were imposed on Scots in autumn 2021, there was abundant evidence that vaccines did not stop infection and transmission. This should have blown the bottom out of the case for vaccine passports. That it failed to stop them is a disgrace.

Irrespective of whether one agrees with his conclusions or not, Croft is to be congratulated for addressing the core question: did the government’s restrictions, deployed at great cost and societal disruption, work?

The fact that he has even asked this question stands in contrast to the groupthink on display at the UK inquiry, presided over by Lady Hallett. Its first theme, examining ‘Preparedness and Resilience’, concluded last month. During the hearings, witnesses were indulged in long meanders through Brexit and Tory / Lib Dem austerity. This was despite the obvious fact that adjacent EU countries not previously governed by David Cameron and Nick Clegg experienced similar travails with the virus.

Witnesses also said that Britain had prepared for the wrong type of pandemic, with all of our plans anticipating an influenza pandemic rather than a coronavirus pandemic. But if coronavirus and influenza pandemics were so obviously different, scientists wouldn’t still be arguing about whether the 1889-94 ‘Russian Flu’ – which was comparable to Covid in terms of mortality – was a form of influenza or a coronavirus.

Unsurprisingly, Croft’s report hasn’t gone down well with the lockdown-supporting press in Scotland. He has been attacked as being ‘not an expert’ in viral pandemics. I don’t know Croft and hold no personal brief for him, but his CV indicates a much longer experience of microbiology-related public health than, say, public-health academic Devi Sridhar, who exerted much influence on Scotland’s Covid response. Military medicine – where he spent his career – takes a great interest in epidemics. They have stopped many armies, from Charles VIII at Naples (syphilis) to Admiral Vernon at Cartagena (yellow fever).

No Western public-health agency advocated lockdowns for a respiratory viral pandemic before 2020. The approach was adopted ad hoc during the Covid pandemic because, as Professor Neil Ferguson (who has scant prior coronavirus experience) infamously told The Times, the government realised it could ‘get away’ with a China-style lockdown after Italy imposed one in February 2020.

It is telling that Scottish commentators no longer even try to say that Scotland’s lockdowns were a success, or that its passport-backed vaccine compulsion was wise. There is too much evidence to the contrary, just as there is ample evidence that lopping the bottoms off classroom doors would have been stupid, too.

I sincerely hope that Scotland’s inquiry reflects upon this. And that Lady Hallett reads Croft’s report. It might just refocus the UK inquiry on the questions that really matter.

David Livermore is a retired professor of medical microbiology.