Part One – Measure the Ripples, Not Just the Splash

Ten steps to effective decision-making

Part One in Paul Dolan’s six-part series ‘Making Policy Better‘

Whether you fully supported the government’s measures to slow the transmission of COVID-19, or considered some of them to be a bit over the top, we should all agree that there are important lessons for how to respond to future crises. Indeed, there are lessons that come out of Covid-19 for how to make better policy decisions in calmer times, too.

During the last year, around the world, the dominant response to the pandemic was lockdown. Acting primarily on the advice of medical professionals, policymakers put death prevention above everything else. Concern for lives at risk from COVID-19 trumped concern for life expectancy in general – let alone life experiences – which were largely ignored. We should never again look at these impacts in isolation.

Most people care strongly about how long they live, as well as about the quality of those lives. And they care about other people’s quality of life as well. To weigh up any policy, we must capture and quantify all the possible short and long-term ripple effects of that policy – not just the size of the splash when it initially hits the water.

If we take as our starting proposition that welfare is improved when we live longer, better lives, it is clear we need to move towards a measure that can better capture changes in both life expectancy and life experience. The effects on how we feel (such as those associated with increased fear) and on what we do (such as obeying orders to stay at home) will both be significant.

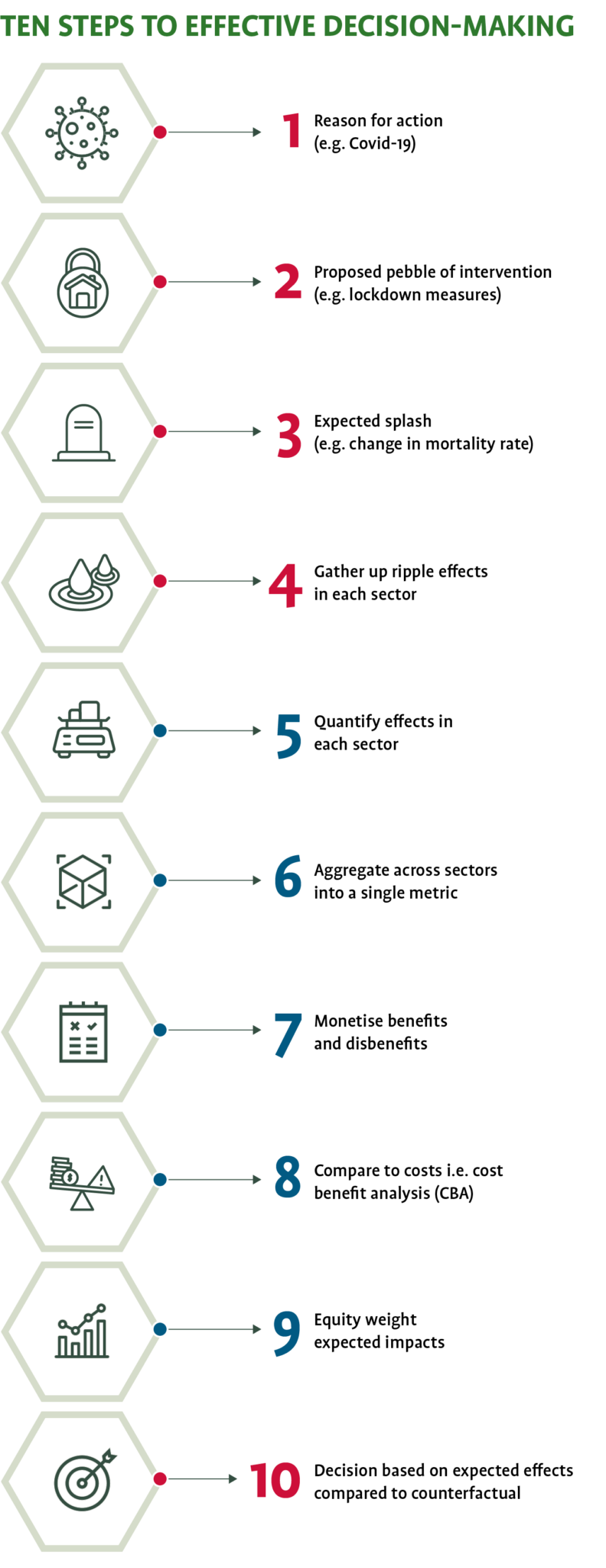

There has been increasing concern about the lack of any kind of cost-benefit analysis (CBA) of the policy responses to COVID-19. It is a vital part of good policymaking to ensure governments can invest in policies that generate the greatest benefit given limited resources. There are 10 steps to creating a full-blown CBA. Each one is a critical component of better informed decision-making (see data box).

Considering where the UK is now, perhaps the most vital step is Step 4: gathering up ripple effects from the policy decisions made during the pandemic to examine the full range of consequences. In simple terms, policymakers have focused their attention on the splash of the pebble of policy on mortality risks (Step 3) to the exclusion of other significant health, economic, and social consequences. These include various negative ripples, and we will examine them in more depth in a future article. Negative ripple effects include deaths and illnesses as a result of hospital beds and medical appointments being taken over by COVID-19 patients, disrupted economic activity, job losses, increased mental health disorders, loneliness, and widening inequalities in educational attainment.

There have also been benefits from lockdown measures including reduced air pollution, increased wildlife, fewer road traffic and workplace accidents, increased take-up of technology, and increased volunteering. Some of these effects might stick into the longer-term too – but which ones? Well, no one knows, of course, and the middle of a crisis is not a time to make predictions. But some of the workplace benefits, for example, are likely to last. If we are to properly evaluate the impact of lockdown policies, we must be alert to their benefits as well as their costs and measure them alongside one another.

We need to go further than just measuring impacts if we are to ensure that we do more good than harm overall. The only way to do this is to bring together the expected impacts on life expectancies and life experiences into a single index.

My belief is that wellbeing over a lifetime needs to be front and centre in the creation of this metric. Saving or prolonging life for some needs to be weighed against diminishing quality of life for others. In the case of COVID-19, the health risks are concentrated amongst older people, so we need to address the ethical justification of asking younger people to make enormous sacrifices for people who aren’t expected to live as long.

Effective decision-making, then, requires an efficient and fair allocation of resources. It is also essential that the processes by which decisions are made are seen to be fair, especially if there is uncertainty about the outcomes. Earlier this year, I recommended creating a well-being commission to advise on what matters to whom and in what ways. This should be a group that represents a diversity of perspective and experience to ensure that all ripple effects across society are properly accounted for in ways that have been absent from global pandemic responses thus far. Once we can measure and analyse these ripple effects more effectively, I also recommend the creation of a wellbeing impacts agency (WIA) with the technical knowledge to create a single metric to capture all costs and benefits.

During the last year, around the world, the dominant response to COVID-19 was to significantly reduce social contacts. This pebble of intervention – perhaps the biggest stone that has ever been dropped into the water – has been assessed almost entirely in terms of its effects on mortality risks. Most of the significant ripple effects which have been set out here have been ignored.

The focus should now be on how to better capture the full range of outcomes of policy and their effects on the distributions of wellbeing across society. We must also consider the processes by which decisions are made so that we can ensure that future harms are minimised.

Paul Dolan is a Professor of Behavioural Science at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is the best-selling author of Happiness by Design and Happy Ever After, as well as the host of the new Duck-Rabbit podcast. www.pauldolan.co.uk.

Any content is provided for your general information purposes only and to inform you about [publicly available information relating to COVID-19 and various government level strategies for addressing the pandemic provided by researchers and other third-party websites that may be of interest], but has not been tailored to your specific requirements or circumstances. It does not constitute technical, financial or legal advice or any other type of advice and should not be relied on for any purposes. You should always use your own independent judgment when using our site and its content.