Censorship is unacceptable in democracies – It also disqualifies the “We didn’t know” argument

I am a historian of communism and post-communism by trade, especially of Czechoslovakia, and, over the years, have learned several useful lessons applicable to any situation, including the Covid-19 pandemic years. My work has focused on revolution (or its absence), the micro-politics of repression and reward that maintained communist regimes, and the re-writing of history to fit narratives of victimhood.

What does this have to do with Covid? More than you would first assume. In a recent article of mine, Surveillance Society: From Communist Czechoslovakia to Contemporary Western Democracies, I discuss some of the parallels. I argue that the use of censorship and suppression of dissent, both central pillars of authoritarian rule, also occurred during Covid and is eerily similar to communist practices. The control of information enforces ideological conformity, manipulates the media, enables surveillance and fear, and is magnified by our new technological tools.

We embraced Covid authoritarianism with ease. Indeed, we still hear public calls to monitor and even censor social media on multiple issues, as the latter are accused of promoting hate speech by failing to filter and delete objectionable posts. As a result, various authorities, including the EU, demand an ever stricter censorship of content by social media companies. What is the result on freedom of speech and academic debate?

The notion that censorship curbs the poisoning of the public sphere by hate speech, fake news, or conspiracy theories is questionable; on the other hand, censorship is very effective at curbing critical perspectives on various governmental policies, in other words at controlling legitimate political opposition. During Covid it became rapidly obvious that “fighting the pandemic” became a guise for controlling public speech on the best way to fight the virus. Let us take a look at a personal example.

A personal story of censorship

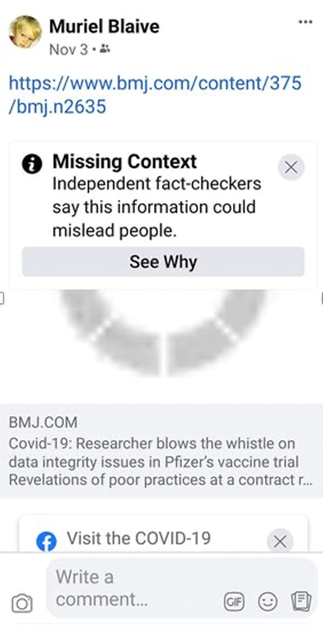

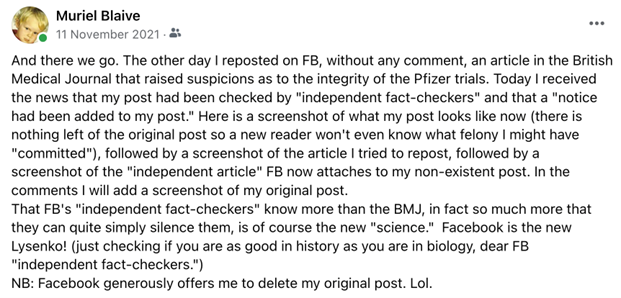

On 3 November 2021, I reposted on Facebook without comment an article published by the British Medical Journal. This article was entitled “Covid-19: Researcher blows the whistle on data integrity issues in Pfizer’s vaccine trial.” Here is the screenshot of my post:

It was instantly covered by the banner “Missing Context. Independent fact-checkers say this information could mislead people.”

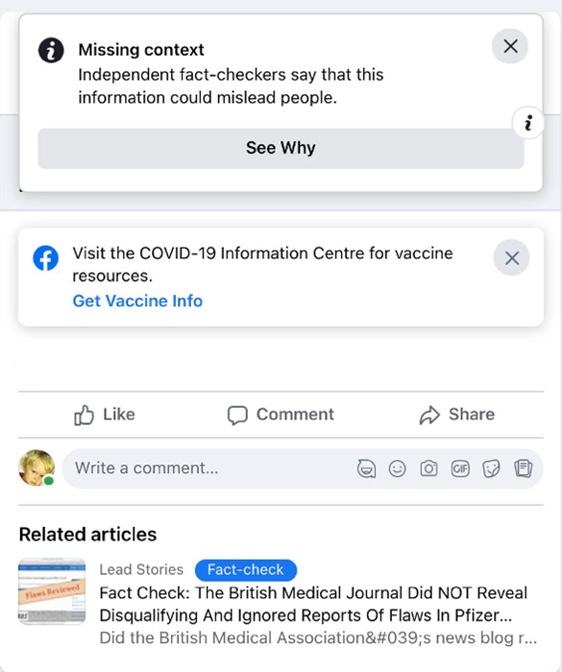

On 11 November 2021, eight days later, I received a further notice from Facebook according to which my post had now been fully assessed by “independent fact-checkers.” It was accompanied by a link toward a “related article” entitled “Fact check: the British Medical Journal Did NOT Reveal Disqualifying and Ignored Reports of Flaws in Pfizer COVID-19 Vaccine Trials.”

The article was authored by Dean Miller, the managing editor of a website called Lead Stories. Lead Stories defines itself as a “U.S. based fact checking website that is always looking for the latest false, misleading, deceptive or inaccurate stories, videos or images going viral on the internet.” It was one of the companies subcontracted by Facebook to rate its users’ posts for misinformation, responsible for up to half of Facebook’s fact checks. Here is what my post now looked like – it was utterly unrecognizable, and its topic was not even visible anymore:

When censors appoint themselves

The fact-checking of this post is the result of a policy dictated by the “Trusted News Initiative”, a consortium of mainstream media that focused, according to BBC Director-General Tim Davie, on “combatting the spread of harmful vaccine disinformation.” Launched in 2019 and reactivated on 10 December 2020 in view of the imminent rollout of the COVID vaccine, it stated: “The Trusted News Initiative partners will … work together to expand our framework and ensure legitimate concerns about future vaccinations are heard, whilst harmful disinformation myths are stopped in their tracks.” Founding members of the consortium are AP, AFP, BBC, CBC/Radio-Canada, European Broadcasting Union (EBU), Facebook, Financial Times, First Draft, Google/YouTube, The Hindu, Microsoft, Reuters, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Twitter, and The Washington Post.

A crucial question is: who is checking the fact-checkers and their definition of what is “legitimate” and “harmful.” BMJ was not amused. It published a letter to the editor on 5 January 2022 which firmly protested against this Lead Stories piece and debunked the debunking: the letter pointed out that the BMJ article was the courageous work of a whistleblower at Pfizer’s as reported by journalist Paul D. Thacker, and that the FB “fact-check” would have a deterring effect on future potential whistleblowers. It also remarked that it was “not the task of fact checkers to police … titles”, and that this article amounted to “character assassination” by questioning the whistleblower’s credentials.

Finally, the letter opened the wider issue of the politics of surveillance in our societies, to which I have myself contributed on the basis of my knowledge of surveillance practices under communist dictatorships as I pointed out above, noting among others this parallel:

“Critics of the various Covid policies have called public opprobrium upon themselves, when they were not scorned, disgraced, and censored for thoughtlessly endangering the rest of the population – just as the dissidents or would-be ‘rowdies’ used to be under communism, with arguments also pertaining at the time to public sanity and national security.”

Poor journalism

Dean Miller is a journalist; according to his own logic, why should he be more credentialed to assess medical data than a laboratory assistant and a colleague science journalist, or than more importantly, the British Medical Journal itself? The BMJ published a longer academic response to his piece on 19 January 2022 entitled “Facebook versus the BMJ: when fact checking goes wrong.” It pointed out that Dean Miller had substantiated his article with a defense that appears to be coming straight from the horse’s mouth: “The Lead Stories article said that none of the flaws identified by The BMJ’s whistleblower, Brook Jackson, would ‘disqualify’ the data collected from the main Pfizer vaccine trial.

Quoting a Pfizer spokesperson, the Dean Miller piece said that the drug company had reviewed Jackson’s concerns and taken ‘actions to correct and remediate’ where necessary. A Pfizer spokesperson said that the company’s investigation “did not identify any issues or concerns that would invalidate the data or jeopardize the integrity of the study” (emphasis added.)

To take Pfizer at face value on such an important matter is a grave ethical and professional failure on the part of a “fact-checker.” But the BMJ response raised yet another serious issue: Facebook refused to intervene in the matter, claiming that only fact-checkers were responsible for reviewing content and applying ratings. Conversely, Lead Stories replied that it was not responsible for Facebook’s actions. In this Catch-22, no one is responsible and there was, and still is, no independent appeal process in place. In effect, “fact-checkers” have been granted a monopoly on information.

As for myself, I posted a little communist joke to the attention of these “fact-checkers”:

Lysenko was a Stalinist “pseudo-scientist” who rejected Gregor Mendel’s revolutionary discoveries on genetics and who “used his political influence and power to suppress dissenting opinions and discredit, marginalize, and imprison his critics, elevating his anti-Mendelian theories to state-sanctioned doctrine.” Alas, Lead Stories clearly missed the reference and failed to censor my little joke.

On the other hand, I was kindly offered by Facebook to remove my own post with the BMJ link (!) As I refused to do so, I (and all those in the same situation) have been shadow-banned on Facebook ever since. We could not be completely banned because an article in the BMJ is hardly fake news, but shadow banning was the alternative measure devised to punish those who challenged the official narrative. This means that to this day, my Facebook friends hardly see my posts, which then get zero or very few likes, even though I completely stopped posting on Covid after this censorship episode. Since I have nowhere to appeal and the situation has not changed in two-and-a-half years, I progressively migrated to Twitter, where I have occasionally flirted with a million impressions a month.

Moreover, until around summer 2023 Facebook also censored my memories on Covid topics so I could not see my own past posts. In good Stalinist fashion, the social media company had endeavored to rewrite not only the future, but also the past. This reminded me of how the writer Milan Kundera narrates in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting that communist leaders who fell into disgrace were retroactively airbrushed from official pictures. In one great scene, a leader vanished from a group picture but his hat, which he had lent to another more powerful leader, who later ordered his execution, remained on the picture – on the leader’s head. As Kundera wrote: “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” As history could also have told “fact-checkers”, Stalinism is inevitably followed by destalinization – and my Facebook memories are now back.

Censorship is incompatible with science

Censorship matters, even on such an anecdotal scale, because it enables authoritarianism and repression. It is easy to pretend that a “scientific consensus reigns” when anyone thinking otherwise is silenced.

The primary opposition to the official Covid narrative on lockdowns, the Great Barrington Declaration, which promoted focused protection and boasts almost one million signatories, was derided in the mainstream media, when it was mentioned at all. Anthony Fauci, the much-publicized director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, called it “nonsense” and “dangerous.” Its three authors, Prof. Martin Kulldorf from Harvard, Prof. Sunetra Gupta from Oxford, and Prof. Jay Bhattacharya from Stanford, were famously called “fringe epidemiologists” by the director of the National Institutes of Health, Francis Collins. Hubris quickly follows in the footsteps of censorship: a year later and as the efficacy of lockdowns became seriously contested, Dr Fauci immodestly claimed that “Attacks on me, quite frankly, are attacks on science.”

What is science, short of being “Anthony Fauci” and his multiple contradictions? How do we recognize a scientific endeavor as opposed to a political one? For historians of communism, these are familiar questions: does historical truth even exist, and how do we establish the difference between a scientific argument and an ideological one? In an article I wrote on historical methodology which I will paraphrase here, I invoked Karl Popper, the famous philosopher of science who pioneered a definition of the scientific method. As a young man, Karl Popper had witnessed how the Austrian Communist Party sacrificed nine comrades to police bullets in 1919 only for the Party to fulfil its doomsday predictions on “historical materialism” (i.e. on capitalist police enforcing violence against the working class), an ideology which it claimed was a “science.”

Such cynicism taught Popper that science had to be ethical in order to be protected from abuse and manipulations, and he became obsessed with defining the difference between science and ideology. This is how he established the criterion of falsifiability: for a theory to be validated as science, it must submit itself to the possibility of concrete objections that attempt to falsify it. The notion of scientific truth is, by definition, momentary and fleeting – a concept is true only until it is proven untrue, and it must itself provide material to be “fact-checked”, as we would say today (i.e., its sources and its reasoning must be explicit and open to criticism).

Hence when there is no debate and no exchange, there is no science, nor is there any democracy. This is why censorship is fundamentally incompatible with science.

Censorship also enables self-censorship

Censorship also crucially enables self-censorship. As my colleague, Libora Oates-Indruchová, has shown in her masterwork on censorship in late socialism (pictured below), censorship inevitably leads to what historians of communism call the “social contract”, i.e. a form of negotiation between social actors and the authorities to determine what behavior and public speech are acceptable or unacceptable. The regime tries to impose as much censorship as society will tolerate without protesting, while society tries to speak out as much as possible without provoking the regime. While searching for the limits of acceptable canon, social actors resort to self-censorship. Yet for obvious reasons, self-censorship is the very opposite of progress in science.

In a situation of heightened scientific uncertainty, as was the case with Covid, it was not only politically unacceptable, but also scientifically extremely damageable, to silence any scientist who might have had productive doubts.

Conclusion: “We were wrong, but we didn’t know” is a fallacious defense

As the Covid official narrative progressively unravels, one domino of the pandemic dogma after the other is falling. In January 2022, Fauci co-authored an article acknowledging the inefficacy of the Covid vaccine in preventing transmission and re-infection. Various health authorities, for instance, the French head of the Covid task force, Prof. Delfraissy, acknowledged that authorities knew since the beginning that the vaccines would not curb transmission even though this was a major public health argument to convince people to take the vaccine and mandate it across the world. Neil Ferguson, the author of the famous Imperial College model that predicted millions of dead without lockdown, denied urging for a lockdown. Boris Johnson blamed the lockdown on his advisors. Former President Trump famously claimed “I don’t take responsibility at all.” One of his advisors claimed, in turn, that his Covid policy was a debacle. The UK Covid inquiry estimated that the tough lockdown had failed children. Andrew Cuomo, the governor of New York and head of the liberal left opposition to President Trump, made a plea for having done what was possible in an atmosphere of disinformation. Former NIH director Francis Collins admitted on the lockdown policy that “Public health people had a very narrow view of what the right decision is”, and “We were not really thinking about the consequences (of the lockdown) in communities that were not New York City or some other big city.” Anthony Fauci himself stated on ABC News that he had “nothing to do with closing down schools.”

Scott Galloway, a New York University professor who had been a passionate advocate of lockdowns and masks, claimed on Real Time with Bill Maher (HBO) on 27 October 2023:

“We were all operating with imperfect information and we were doing our best. Let’s learn from it, let’s hold each other accountable, but let’s bring a little bit of grace and forgiveness to the shitshow that was Covid.”

Scott Galloway indeed operated with “imperfect information” for the good reason that his favorite outlets censored any criticism of the Covid official policy and derided them as “fake news”, while calling for ever more censorship.

But what he could and should have known is that censorship is unacceptable and shameful in a democracy, especially during a crisis when collective intelligence must be crucially mobilized.

Without censorship, alternative policies could have been discussed since the beginning. University professors such as Martin Kulldorf (Harvard), Scott Atlas (Stanford), or Aaron Kheriarty (Irvine), but also all the small medical personnel, anonymous doctors and nurses, who dared to speak out and were ostracized, if not fired or led to resign, deserve much more “grace and understanding” than Scott Galloway does, not to mention that they deserve their jobs back.

A reckoning of the Covid policy failures is all the more necessary and urgent that the censorship tools adopted under the pretext of the virus are still in place and remain at the disposal of all governments. If these repressive tools fall into even worse hands, as appears almost inevitable considering the economic crisis and popular discontent unleashed by the lockdowns and other concurrent global crises underway, the consequences for democracy and for scientific inquiry are potentially devastating. And that should make us all concerned.

(An earlier version of this text was published on my Substack: here)

About the Author

Muriel Blaive is a historian of communist and post-communist Central Europe. She is currently an Elise Richter fellow at the University of Graz (Austria). You can follow her on X (formerly Twitter) at @MurielBlaivePhD