Media backs Supreme Court’s Covid-era censorship ruling

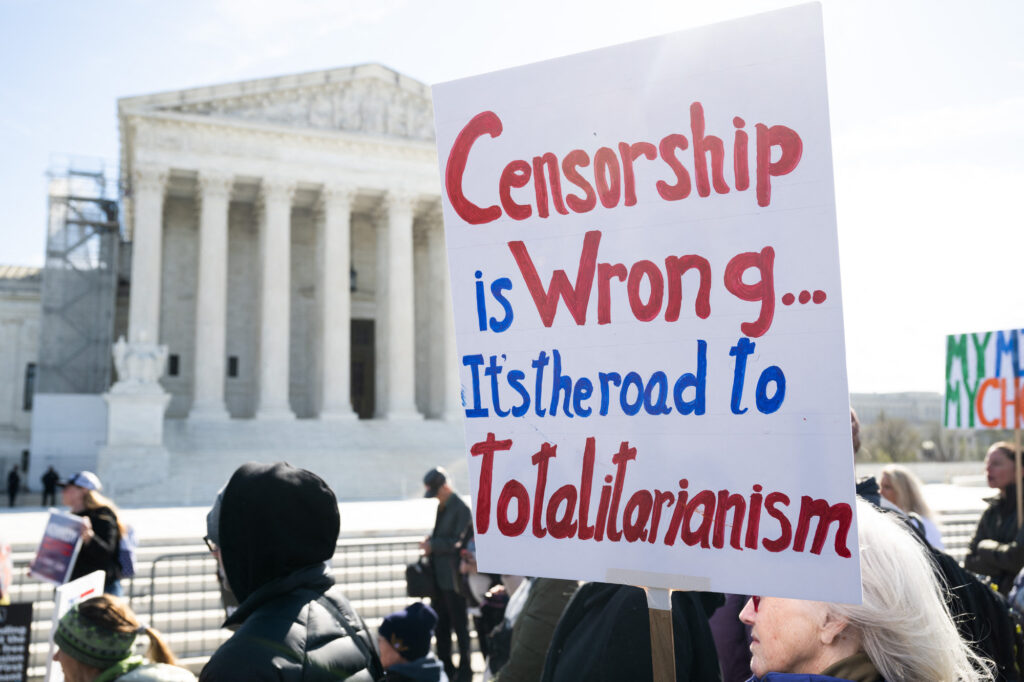

The US Supreme Court this week ruled against (6-3) plaintiffs in a historic free speech case. Murthy v. Missouri alleged that Biden administration officials engaged in a wide-ranging censorship campaign during the Covid pandemic, with the goal of stifling dissent on lockdowns, vaccines, natural immunity and masks.

Mainstream outlets — including the New York Times, Guardian, Vox, and CNN — reported positively on the decision, claiming that the court had effectively “approved” of the government’s actions, including by the CDC and FBI, in requesting the removal of posts on Facebook and X and persuading changes to content moderation policies.

Really, though, the case and the Court’s decision reflects a variety of procedural issues and evidential standards that also raise questions about how to define and prove a particular individual has been harmed by federal censorship efforts — what has become known as the “censorship-industrial complex”.

First, the decision is mired in procedural issues. It focused on an emergency ruling to stop the federal government communicating with social media companies (called a preliminary injunction). It ruled that the plaintiffs did not have “standing” to sue because they could not establish proof that the government had directly coerced social media companies to censor them. The legal criteria also depends on establishing the possibility of future harm and the court ruled that, essentially, the Covid censorship of 2021 is not the same in 2024.

Second, the Court’s decision also had to do with the burden of proof. The majority opinion re-articulated a need for precision and particularity; the plaintiffs needed a smoking gun, evidence to connect the dots. The Court argued that the range of claims was at times confusing. Twitter and Facebook were moderating — censoring — Covid content independently from the Biden administration. Covid-era censorship, after all, also widely occurred under Trump. And federal officials are always communicating and persuading social media companies, so what’s the big deal?

Free speech advocates, such as Matt Taibbi and the New Civil Liberties Alliance (which was involved in the case), pointed out that the Court’s decision will embolden federal officials to engage in future pressure campaigns. As long as the government can’t be seen as targeting a single individual, it can engage in censorship activities. This was made clear by Justice Samuel Alito and others in the dissenting opinion: “If a coercive campaign is carried out with enough sophistication, it may get by. That is not a message this Court should send.”

Additionally, the evidential standard ignores the ways that censorship regimes work in practice: it is rare that such work is explicitly stated about one individual. During Covid, these were often subject- and narrative-based bans. Coercive censorship also works dynamically with other group pressures and, in the pandemic, a wider climate of fear and conformity.

Ironically, this can be seen in the mainstream press’s coverage of the Court’s decision, where the plaintiffs are repeatedly labelled “far-right”, with no mention of their academic and medical credentials. The fact that the case brought together Republican attorney generals of Missouri and Louisiana and the founder of the Right-wing media outlet Gateway Pundit with four other plaintiffs shaped this media narrative.

Yet the world’s preeminent scientific journal, Nature, also published a news piece this week calling the plaintiffs “conservative activists”. Numerous opinion pieces in Nature continue to promote a certain “brand”, or cottage industry, of misinformation research (questioned by others) that exerts huge influence in government circles: the “censorship-industrial complex” does not exist and content moderation is necessary to “protect democracy”.

Yet three of the five plaintiffs are widely recognised scientists and physicians. Prof. Jay Bhattacharya, from Stanford, was blacklisted and shadow-banned on Twitter after Dr. Anthony Fauci called for a “devastating takedown” of the Great Barrington Declaration. Prof. Martin Kulldorff (previously at Harvard) and Prof. Aaron Kheriaty (previous head of the Medical Ethics Program at UCI) lost their jobs and experienced censorship partially due to their position on vaccination and natural immunity.

The majority opinion of the Court and other commentators, including from Nature, had little to say about the thin line between the bully pulpit (persuasion) and the use of “coercion” proper by federal officials, let alone larger questions about other group pressures.

At the heart of the case, then, is a question about the nature of modern censorship and the paper trail (or lack thereof). As the case returns to the lower court, the plaintiffs are likely to pursue discovery requests to search out such evidence — traceable links — in government communications, something that may take years to work out.

But there is another way. The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) recently released a draft bill outlining, among other things, the need for government accountability during contact with social media companies including a public searchable database that would allow the public access to such communications. It’s a start. There is now an opportunity for Congress to take action against the incentive for federal officials to pressure social media companies to censor.

Follow Kevin Bardosh on X (formerly Twitter) @KevinBardosh